Crime writer pushes for progress in rape-kits backlog after her assault

10/20/2016 11:02 am PDT

Just how far would you go to get justice? It's a question Emily Winslow asked herself hundreds of times, and every year it seemed like she would never find the mystery man who attacked her.

For more than half of her life, crime writer Emily Winslow lived with a secret second name: Jane Doe, the unnamed victim of a horrible attack.

It was January 1992 in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Emily Winslow, actresses Donna Lynne Champlin and Kali Rocha were all students in the ultra-exclusive drama conservatory at Carnegie Mellon University. Emily lived alone in the upscale neighborhood known as Shadyside.

What the students didn't know is that there was a dangerous predator stalking those streets, and he set his sights on Emily.

"It was Christmas break my junior year and I needed to go out and get change for the laundry machine, and as I went out I saw a man I'd never seen before kind of hanging around near the building," said Winslow.

"He didn't look comfortable and as he started walking toward the door, I thought I won't hold the door for him, you know, like you'd normally do, and so I tried to let it swing shut behind me but it was one of those pneumatic closers that closes very, very, very slowly and you can't pull it, and he caught the door right behind my ear, I remember his hand coming right here, and he caught the door and came in behind me," said Winslow. "So he went upstairs and he waited. There's a stairway, and he hid in there.

"I went upstairs and I unlocked my door and he jumped from the stairs and he pushed me inside and closed the door.

"When he left, I jumped up and locked the door, that was the most important thing to do right away, and then I called 911 and I knew from reading women's magazines that you don't wash, you don't change your clothes, you don't do anything you just call 911 and you wait," said Winslow.

Pittsburgh Police Detective Bill Valenta met Emily at the hospital and was already impressed with her demeanor just hours after being savagely attacked in her own home.

"She was remarkably composed through it, she was able to walk me through exactly what happened," said Valenta.

Emily called her friends and told them the horrible news. Adding to the pain, Emily may not have been the attacker's only victim.

"Apparently a student from the University of Pittsburgh had been attacked, he had said the same thing to her, so they very quickly had the idea that this was not a singular attack," said Winslow.

Days turned into months -- months turned into years. The case had gone cold. Det. Valenta moved out of sex crimes investigations. Emily Winslow and her friends graduated school. Winslow moved to Cambridge, England and became a successful crime writer. But every year, on or around the anniversary of her attack, she would call Pittsburgh Police.

At the time of Winslow's attack, DNA evidence was gathered from her -- but her rape kit would sadly end up in the an all-too-common black hole of justice.

Dr. Karl Williams oversees the crime lab that covers Winslow's case.

"Every forensic laboratory in the country has some sort of backlog, because none of them are funded adequately," said Williams.

In fact, a recent study says at least 70,000 rape kits lie untested in the United States -- that's tens of thousands of potential predators still walking the streets.

Emily Winslow was determined that she wouldn't become just a number. She hounded Detective Daniel Honan. He then linked up with Detective Aprill-Noelle Campbell, who was working a very similar cold case from the same area.

"So my evidence kit, which was collected Sunday, January 12, 1992, finally was given to the crime lab in the fall of 2013," said Winslow.

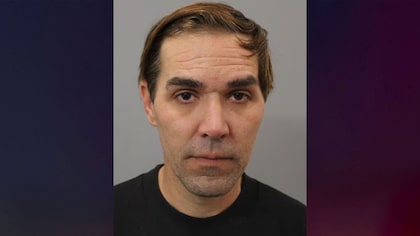

The information was then run through the national DNA index system CODIS. And there was a match: 61-year-old Arthur Fryar, who was now living in Brooklyn, New York. Fryar, a convicted felon, was arrested and booked, charged with the sexual assault of two women, including Emily Winslow.

But the journey of justice would hit an unforeseen and crushing roadblock.

"I got a Skype call from the new A.D.A., and he looked very sad," said Winslow. "Then he had to tell me that he had discovered something terrible about our case."

Even though they had hard DNA evidence, and detectives say Fryar had reportedly made admissions of guilt to them, the case was dismissed. A legal loophole had allowed the statute of limitations to run out.

It's now been two years since Fryar escaped two trials for sexual assault.

Instead of allowing herself to be victimized again, Winslow did what she knew best: She wrote a tell-all new novel, Jane Doe January: My Twenty-Year Search for Truth and Justice.

Emily Winslow has been very outspoken about the problem of backlogged rape kits that still need to be tested. And she's fighting for federal grant money to help try to put more sexual predators behind bars.